How Pathways and Bridleways Connect Communities and Green Spaces

Funny thing about footpaths. You can live somewhere for years and barely notice the narrow cut-through behind the houses, or that bridleway skirting a farm boundary you’ve never bothered exploring. One rainy Tuesday you follow it on a whim and suddenly you’re wandering through meadow edges, then a woodland belt, then out by a playground you didn’t even know existed. It’s odd how these quiet threads stitch places together more tightly than most people realise.

And that’s the heart of it. Pathways and bridleways do far more than provide something solid to walk on. They pull communities towards each other. They open up forgotten bits of land. They give cyclists a safer route than squeezing past buses on the A roads. They’re small things that lead to big changes. Sort of like the way a shortcut to the shops becomes a social meeting point if enough people start using it.

Anyway, before I ramble too far off the track, let’s get into what these routes really mean for people, landscapes, and the in-between spaces that often get overlooked.

Introduction: Why Local Routes Matter More Than People Think

Odd as it sounds, I’ve always found the most interesting parts of a town aren’t the high streets or the housing estates but the scraps that sit between them. The footpath behind the garages. The quiet lane linking two villages. The bridleway that runs behind allotments before dipping into a copse. Once a route exists, people use it. Once they use it, it becomes part of everyday life without anyone formally acknowledging it.

Across the UK you’ve got thousands of these green connectors. Some formal, some half-forgotten. Some maintained, others a bit of a faff to walk along after heavy rain because someone’s forgotten to compact the surface properly. And yet they’re irreplaceable. They carry dog walkers, schoolchildren, wheelchair users, cyclists, riders… the whole mix.

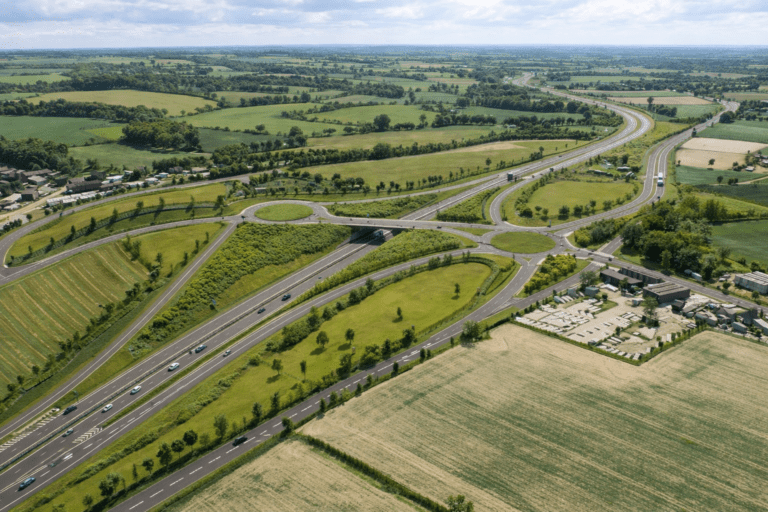

There’s a practical side to this too. Safe active travel routes reduce short car trips. Fewer cars on the road means cleaner air, calmer streets, and marginally less road rage at 5pm when everyone from Derby to Chesterfield seems to be on the same roundabout. It all adds up. Quietly, almost unnoticed.

For contractors and councils working on footpath schemes, the challenge is designing routes that fit the land as naturally as possible. You can see how we approach this in our work on pathways and bridleways, explained more on our main service page about pathways and bridleways. It’s all about practicality, long term durability, and environmental sense.

How Routes Connect Communities in Daily Life

Strange thing, but when you start mapping the places where people walk, cycle, and ride regularly, you notice something. Communities don’t grow around roads. They grow around connections.

Footpaths as social glue

Anyone who’s lived near a good network of paths knows what I mean. You bump into neighbours. You recognise the regular dog walkers. Kids walk to school in small groups. The paths become these casual social corridors where you exchange nods, or chat about the weather if you’ve run out of other things to talk about. Properly British small talk.

In my experience, a well positioned path can make a new housing development feel less isolated. Not because it’s fancy but because it links people to the older parts of town without them needing to cross big, noisy junctions.

Bridleways bring riders into the mix

Horse riders often feel forgotten in planning conversations. Yet a single bridleway connecting village outskirts to a country lane can give riders a safe, predictable route that cars don’t dominate. Bridleways also end up being used by walkers and cyclists more than people expect, mostly because they usually have generous width and softer surfacing.

Cycling routes as alternative arteries

Some cycle routes feel like afterthoughts. Others become the main way locals travel between estates. When a bridleway or shared path provides a clean link between schools, leisure centres, parks, and neighbourhoods, it changes how people move. You know that feeling when you realise it’s quicker to get somewhere on foot or bike than by car? These routes make that possible.

How Pathways Connect People With Green Spaces

Every town has green pockets. A park here. A strip of woodland there. A disused railway line that’s now scrub habitat with birds you can hear but never quite see. what’s missing in many places is the network that ties them together.

Safe access to nature

You’d be surprised how many people avoid parks simply because the only way in is a busy road crossing. Add a quiet footpath and suddenly the place feels accessible. It’s not rocket science. Even a simple crushed-gravel path can encourage families to wander further.

Mental wellbeing benefits

I’ve noticed that during lockdowns people rediscovered their local footpaths with a strange enthusiasm. They needed green space. They needed breathing room. And most of them weren’t heading to vast nature reserves. They were walking through local corridors of green they’d overlooked for years. Something about that stuck, I reckon.

Reducing pressure on fragile habitats

By giving people clear, well surfaced routes, you gently guide them away from sensitive areas. Without being heavy handed. People naturally follow paths that are comfortable to walk on. That helps protect nesting birds, wetland vegetation, wildflower areas, and other easy-to-damage spots.

Inclusive Access: Making Sure Everyone Can Use These Routes

A footpath that only half the community can use isn’t doing its job. You need gradients that don’t feel punishing, surfaces that don’t turn into slippery sludge in November, and widths that allow wheelchairs, prams, mobility scooters, and bikes to pass without awkward shuffling.

Accessibility challenges that often get overlooked

- Surface firmness

Wheelchair users need firmness. Horses prefer a bit of give. Cyclists want predictability. Balancing these isn’t easy. - Width and passing points

Some paths feel like walking along the edge of a cliff even though you’re just passing a hedge. Simple widening solves most of that. - Gradients

Yorkshire and Derbyshire routes, for example, need careful planning to avoid steep hills. You can’t just follow the most obvious line. - Drainage

One downpour and an inaccessible path becomes unusable for days. And once people give up using it, you’ve lost them for good.

A quick comparison table

| User Group | Path Needs | Common Barriers | Good Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Walkers | Stable footing | Mud, steep steps | Permeable gravel, gentle gradients |

| Cyclists | Smooth predictable surface | Potholes, sudden barriers | Resin bound paths, clear signage |

| Horse riders | Softer, non slip surfaces | Narrow pinch points | Well compacted stone, wider bridleways |

| Wheelchair users | Firm consistent surface | Ruts, cambers | Bound surfaces, no awkward cambers |

| Families with prams | Wide flat routes | Stiles, trip hazards | Kissing gates, widened entrances |

Something for everyone, basically.

Environmental Benefits: Quiet but Important

It’s easy to assume that adding more paths interferes with nature, but the opposite is often true when routes are designed with care.

Reducing habitat disturbance

Paths concentrate foot traffic. If you give people a clear, comfortable route, they’re far less likely to make their own informal cut-throughs that damage vegetation. You avoid those messy desire lines that slowly widen over time.

Connecting wildlife corridors

Oddly enough, some verge edges along bridleways become excellent microhabitats for insects, small mammals, and even reptiles. Warm gravel, long grass fringes, south facing banks… it’s a small ecosystem if you look closely.

Better soil protection

Compaction is a huge issue in sensitive sites. A properly constructed sub base spreads the load so the topsoil beyond the path stays healthy. Healthy soil means stronger plants. And stronger plants hold the landscape together.

Pathways as Part of Active Travel Networks

A surprising number of short car trips in the UK are under two miles. The kind of distance easily walked or cycled if you’ve got a pleasant route. But if the only option involves crossing two roundabouts and dodging lorries, you’d choose the car too. Doesn’t make you lazy. It makes you sensible.

How well designed paths reduce traffic

- They provide predictable, continuous access between neighbourhoods

- They make cycling feel less stressful

- They make walking routes enjoyable, which is half the battle

- They reduce school run congestion (a big win for air quality)

Little improvements, huge cumulative effect.

Community Identity and Sense of Place

It might sound a bit soft, but paths give places texture. You see it in coastal towns where cliff paths overlook the sea. You see it in old mining towns where routes follow the old tramways. Even modern estates feel more grounded when they have green lanes threading between streets.

I was going to say that these routes create identity, but no, not quite. It’s more that they preserve existing identity while subtly opening places up. People use them to reach village halls, car boot sales, allotments, football pitches, Sunday markets… all the community stuff that makes somewhere feel lived in rather than just built.

Frequently Asked Questions

These tend to come up all the time, so here’s a simple table that keeps it tidy.

| Question | Quick Answer | More Detail |

|---|---|---|

| Are shared paths safe for walkers and cyclists | Yes with spacing | Clear surfacing and sightlines prevent conflicts |

| Do bridleways need different materials | Usually | Horses need softer grip, so mixed aggregates work best |

| Can paths boost local economies | Very much so | Increased footfall near shops, cafes, heritage sites |

| What about maintenance | Manageable | Good design makes long term upkeep easier |

| How wide should community paths be | Depends | Often 2 to 3 metres, but context matters |

Side Note: A Tiny Rant About Poor Routing

Sometimes you see a path that climbs a bank for no reason, drops down again, and skirts a muddy hollow despite a perfectly good alternative three metres away. Drives me mad. Routing is as much an art as a technical process. If it feels wrong when you walk it, it probably is.

In places like Nottingham’s new developments, you can often tell when a path has been sketched in after the houses were drawn, rather than before. It always ends up less intuitive like that.

The Community Ripple Effect

Start with one good route. Then extend it slightly. Add a spur to a nature reserve. Then a short link to a school. Then join it up with a bridleway out to the next village. Before long you’ve created something much bigger than its component parts.

People start using bikes instead of cars for short journeys. Kids have safe ways to roam. Older residents feel connected instead of marooned behind busy roads. Volunteers adopt sections to keep tidy. Councils notice the value. It snowballs. Quietly, but surely.

Pulling Things Together

If you strip away all the engineering and the planning policies and the funding bids, you’re left with something beautifully simple. Pathways and bridleways help people move. They help landscapes breathe. And they help communities feel like communities instead of clusters of houses.

I reckon that’s why they matter so much. They’re unspectacular in the best way. They’re grounded in everyday life. You use them without thinking. Until one day you notice the difference they make.

Killingley Insights is the editorial voice of NT Killingley Ltd, drawing on decades of experience in landscaping, environmental enhancements, and civil engineering projects across the UK.