British vs English Wildflower Seeds: What’s the Difference and Which Should You Choose?

Wildflower seeds sound straightforward enough. A packet, a patch of soil, a splash of colour. But if you’ve started shopping around, you’ll have noticed something odd: some mixes are labelled British wildflower seeds, others English wildflower seeds, and a few even spell it out as English wild flower seeds (with the space). So which is right for your garden? And does it actually matter?

The short answer: yes, it does matter — but maybe not in the way you think.

First Things First: What’s in a Name?

It’s easy to assume “British” and “English” are just marketing labels. Sometimes they are. But there’s also a subtle difference.

- British wildflower seeds usually cover the whole of the UK. That means mixes could include species native to Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland, and England. They’re often designed with broad adaptability in mind.

- English wildflower seeds (or English wild flower seeds, same thing) are typically focused on species historically found in England’s meadows, hedgerows, and field margins. They tend to lean towards southern lowland species — plants you’d spot in a chalk meadow in Kent or a roadside verge in Derbyshire.

So, one’s a broader umbrella. The other’s a slice of it.

Why Does It Matter?

Because wildflowers are not all the same. A plant that thrives on the chalk downs of Sussex may sulk in a wet Cumbrian field. And a Scottish montane mix will look completely out of place in a suburban Bedfordshire garden.

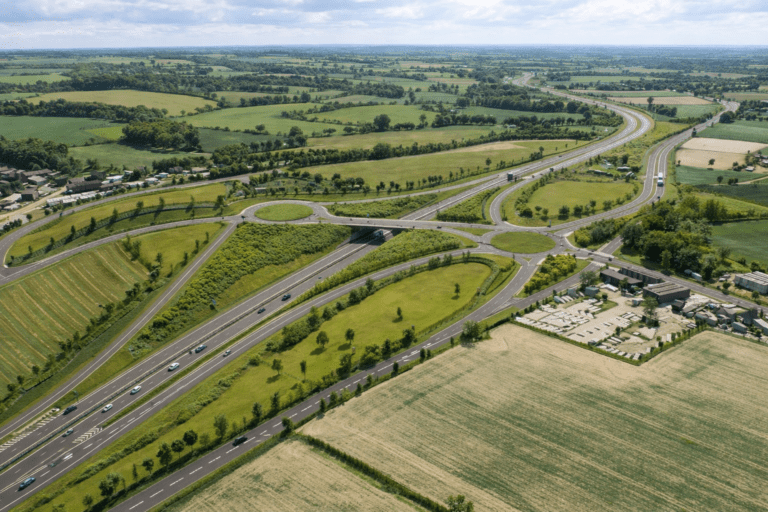

If you want authenticity — a patch that genuinely reflects local ecology — you’ll need to think carefully about what you sow. That’s why some contractors and landscapers (companies like Killingley Wildflower Seeding) specify regionally appropriate seed mixes for their large-scale projects. It keeps things in balance.

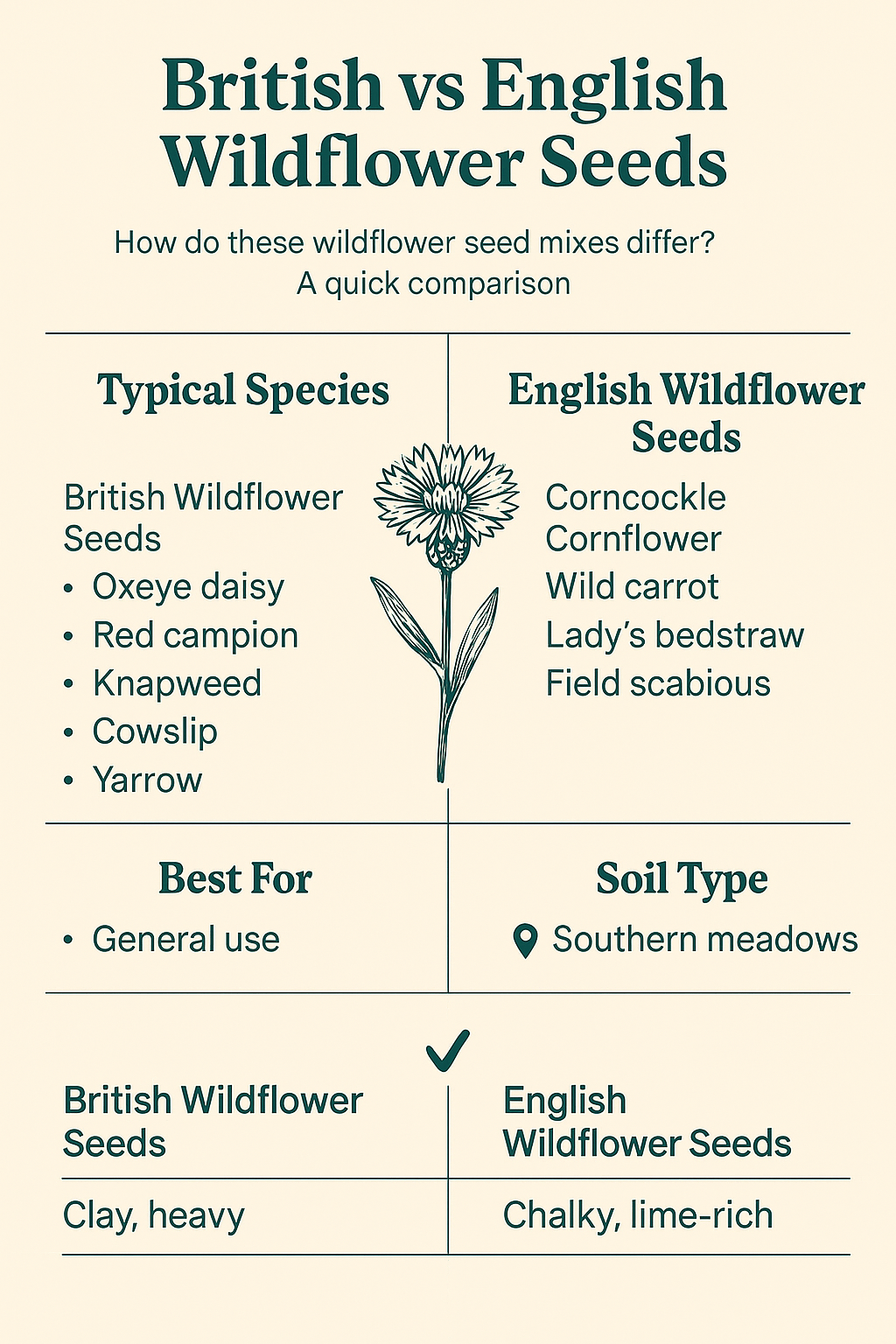

Common Species in British vs English Wildflower Seed Mixes

Here’s a rough comparison. Bear in mind, suppliers vary — but this table gives you an idea of what might crop up.

| Mix Label | Typical Species | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| British Wildflower Seeds | Oxeye daisy, red campion, knapweed, cowslip, yarrow | A blend that works across the UK. Good “all-rounder” for gardens and verges. |

| English Wildflower Seeds | Corncockle, cornflower, wild carrot, lady’s bedstraw, field scabious | More typical of southern English meadows and lowlands. Suits chalky or lighter soils. |

Does that mean you’ll only get those flowers? Not at all. Many species overlap. But the emphasis differs.

Which Should You Choose for Your Garden?

Depends on what you’re after.

- For a cottage garden vibe – English wildflower seeds often give you that romantic, picture-book look. Think poppies nodding by the hedge, scabious swaying in the breeze.

- For a tougher, mixed environment – British wildflower seeds are usually the safer bet. They’re bred to cope with different soils, and they’ll give you variety without too much fuss.

- For authenticity – If you’re restoring a patch of meadowland, you might want a seed supplier that offers county-specific mixes. Some even go hyper-local — seeds collected from within a few miles of your site.

Personally, I’d say if you’re in doubt, go British. It’s less likely to fail. But if you’ve got free-draining chalk or sandy soil and want that southern meadow look, English can be stunning.

Isn’t It All Just Marketing Hype?

Partly. Some companies slap “English” on the label because it sounds quaint and traditional. Others prefer “British” because it implies inclusivity.

But there is a genuine ecological distinction. The Flora of Britain isn’t identical to the Flora of England. Wales has wetter-loving species, Scotland has alpine and montane plants, Northern Ireland has its own mix again. So while the overlap is large, it’s not a perfect circle.

Do Wildflower Seeds Have to Be Native?

Good question. Purists will say yes. Only native species count.

But most garden mixes include a handful of non-native annuals — cornflowers, for example, which were introduced centuries ago but now feel at home. Are they “cheating”? Not really. They’re attractive, pollinator-friendly, and safe for UK ecosystems.

That said, if you’re sowing on farmland or a conservation project, you’ll almost certainly need to stick with native-only mixes.

FAQs About British and English Wildflower Seeds

Will English wildflower seeds grow in Scotland?

Some will, yes. But they might not look authentic, and a few could struggle in wetter or cooler soils.

Can I mix British and English wildflower seeds?

Absolutely. Many gardeners do. Just don’t over-seed — otherwise the stronger plants (usually the perennials) will swamp the rest.

Are they safe for pollinators?

Both British and English wildflower seeds are excellent for bees and butterflies. Just avoid “wildflower mixes” that are really just colourful annual imports (often cheap supermarket packets).

Do I need to prepare the soil differently?

No difference. Both need a clean, low-nutrient seedbed. Clear the weeds, rake it fine, and keep it firm.

Soil Types and Best Fit

Here’s a quick guide that might help.

| Soil Type | Best Fit | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Chalky, lime-rich | English mixes | Many English meadow species evolved on chalk downs. |

| Clay, heavy | British mixes | Broader range copes better with sticky soils. |

| Sandy, free-draining | Either | But English annuals often do especially well. |

| Acidic (peaty, moorland) | British mixes | More tolerant of extremes. |

A Personal Aside

I once tried an “English wild flower” mix in a back garden in Nottinghamshire. It looked gorgeous for one summer — poppies, corn marigolds, cornflowers. But by year two, it fizzled. Wrong soil, too heavy.

Switched to a British meadow mix instead. A bit slower to get going, but by the second year, knapweed and oxeye daisies were buzzing with bees.

So yes, labels do matter.

Final Thoughts

Choosing between British and English wildflower seeds isn’t about right or wrong. It’s about context. What soil have you got? What look are you after? How important is authenticity to you?

If you just want a colourful patch, go British — it’ll cover more bases. If you’re after that classic English meadow look and your soil suits, try English. And if you’re sowing on a scale that matters for conservation, talk to a specialist about regional seed.

At the end of the day, both will give you something lawns can’t: movement, texture, and life. And once you’ve seen bees tumbling in a patch of knapweed, or butterflies hovering over scabious, you won’t look back.

Killingley Insights is the editorial voice of NT Killingley Ltd, drawing on decades of experience in landscaping, environmental enhancements, and civil engineering projects across the UK.