Urban Regeneration Through Green Infrastructure: The Power of Planting and Public Spaces

You can tell when a place has been designed with people in mind. Trees softening hard edges. Planters breaking up concrete. A park that draws people out of their offices for lunch. Green infrastructure isn’t just about planting trees – it’s about how nature and the built environment coexist. And when done well, it can completely change how a place feels.

Urban regeneration is often thought of as bricks and mortar – new housing, retail, transport links. But the real shift happens when green infrastructure becomes part of that equation. It’s not decoration. It’s the life support system that makes regeneration last.

Planting and public spaces aren’t just aesthetic touches – they’re a framework for healthier, more resilient towns and cities.

What Do We Mean by Green Infrastructure?

It’s one of those phrases that sounds technical but isn’t. At its simplest, green infrastructure means the network of green and blue spaces that bring nature into urban areas – trees, parks, green roofs, swales, ponds, verges, even living walls. Anything that contributes to ecology, drainage, or human wellbeing.

Think of it as a city’s natural plumbing and lungs rolled into one. Rainwater gets slowed, filtered, absorbed. Air gets cleaned. Temperatures drop. People relax. It’s the opposite of grey infrastructure (roads, pavements, drainage systems). Instead of fighting nature, it works with it.

You’ll see it everywhere once you start looking – those raingardens outside new developments, the tiny meadow in a supermarket car park, the vines creeping up a library wall. They all count.

For a broader look at how this ties into the wider design of towns and cities, see our section on public realm and urban regeneration.

Why Green Infrastructure Matters in Regeneration

Let’s be honest – not every regeneration project gets it right. Sometimes you see shiny new apartments surrounded by bare tarmac, token shrubs dying in their planters. It’s tidy, but lifeless.

When greenery becomes central to regeneration rather than an afterthought, everything changes. Trees shade pavements, making them walkable in summer. Green roofs and planted courtyards cool dense developments. Urban wetlands soak up floodwater before it hits the drains.

And it’s not just environmental. There’s a social dimension too. People gather in pleasant spaces. Children play. Cafés spill out. Suddenly there’s community where before there was just concrete.

In a way, green infrastructure is the quiet partner in urban renewal – you don’t notice it when it’s good, but you really feel it when it’s missing.

The Power of Planting

There’s something transformative about trees in particular. A single mature oak can intercept thousands of litres of rain each year, cool the air by several degrees, and support hundreds of species. Multiply that across a city and you’re looking at measurable differences in air quality and temperature.

But planting is also psychological. Green views lower stress, reduce aggression, and even improve concentration – there’s plenty of research backing that up. NHS Forest projects, for example, show staff recovery rates improving just through contact with outdoor green space.

And yet, urban trees are often seen as expendable. A road scheme comes along, and suddenly “root conflicts” mean they’re gone. It’s short-sighted. Because every time a mature tree disappears, so does a small piece of the city’s natural capital – the accumulated value of all those quiet benefits.

Public Spaces as the Heart of Regeneration

Planting on its own is good. Planting woven into usable public spaces is far better.

When regeneration includes genuinely public areas – squares, courtyards, riversides – it changes how people relate to their surroundings. Instead of passing through, they stay. They take ownership.

Sheffield’s Peace Gardens are a perfect example. Once a car park, now a civic square that hums with life. Trees, fountains, grassed areas, cafés. It’s not just somewhere to sit – it’s part of the city’s identity.

Similar things have happened in Birmingham’s Centenary Square and Manchester’s Castlefield Basin. Each began as hard, post-industrial environments. Add greenery and human scale, and suddenly they’re inviting.

Public spaces succeed when they’re designed for everyone – families, commuters, older people. When maintenance is built into the plan. And when the space isn’t over-programmed. The best ones let people decide how to use them.

How Green Infrastructure Delivers Measurable Benefits

Sometimes the benefits feel intangible – prettier streets, calmer atmosphere. But there are hard numbers too.

| Benefit | Example / Evidence |

|---|---|

| Reduced flood risk | Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS) can reduce surface water runoff by up to 80%. |

| Improved air quality | Urban trees remove an estimated 2,300 tonnes of pollutants a year across London. |

| Energy savings | Shade from street trees can reduce building cooling costs by 30%. |

| Increased property values | Homes near well-maintained parks are worth up to 20% more. |

| Mental health improvement | Access to green space reduces the risk of depression by up to 33%. |

These aren’t abstract figures. They’re the real, physical paybacks that come when a place invests in its natural systems.

The Role of Water – Blue Meets Green

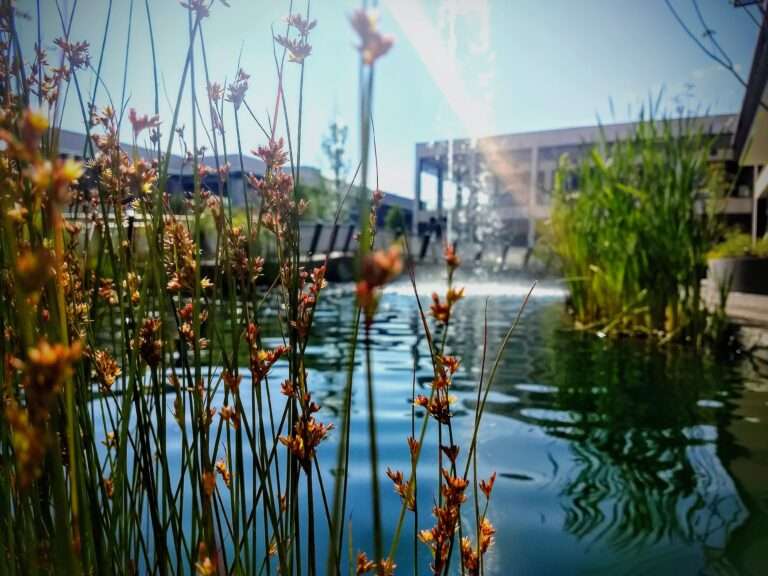

We tend to think of greenery first, but water is just as powerful. Lakes, streams, ponds, even simple rills running through a plaza – they change the character of a place completely.

Water slows people down. It brings sound, reflection, a kind of stillness. But it also works hard behind the scenes. Attenuation ponds and wetlands are becoming standard in new developments because they store and filter rainwater before it reaches the sewers.

The trick is designing water and planting to work together – bioswales lined with reeds, raingardens fed by roof runoff, rills that double as overflow channels. When this network is thought through, it creates resilience. The site becomes part of a living system rather than a sealed surface.

The Economics of Green Infrastructure

Developers sometimes flinch at the cost of green features. Maintenance, planting, irrigation – it adds up. But the return on investment is enormous.

Cleaner air, less flooding, higher property values, healthier residents – it’s hard to put a price on that. And crucially, people want to live and work in greener places.

In my experience, green infrastructure has moved from “nice to have” to “essential” in regeneration schemes. Planning authorities now expect it. The National Planning Policy Framework makes it clear – developments should achieve biodiversity net gain. That means planting and habitat aren’t optional extras; they’re a baseline.

From Grey to Green: Retrofitting Older Areas

Not every area has the luxury of starting from scratch. Many regeneration projects take place in older, built-up districts where every inch of land is already claimed.

That’s where creative design comes in. Turning redundant car parks into pocket parks. Greening flat roofs. Installing living walls on gable ends. Converting wide carriageways into shared spaces lined with trees.

It’s happening quietly across the UK – Salford, Bristol, Glasgow, Leeds. Streets once dominated by cars are being softened with planting and cycleways. People linger longer, spend more, and take more pride in their neighbourhoods.

The challenge isn’t technical – it’s cultural. Convincing stakeholders that trees are infrastructure, not decoration.

Challenges and Contradictions

Of course, it’s not all smooth sailing. Green infrastructure brings maintenance obligations, and councils under financial pressure sometimes struggle to keep spaces pristine. There’s also the question of inclusivity – some regenerated areas risk becoming too polished, pushing out the very communities they were meant to help.

And climate resilience isn’t one-size-fits-all. What works in Manchester’s rainfall doesn’t necessarily suit drought-prone parts of southern England. Choosing the right species, the right system, is crucial.

Still, even with these caveats, the alternative – endless grey, no shade, no biodiversity – just isn’t viable anymore. Cities without greenery are cities without life.

The Human Element

Whenever I visit a new development, I watch how people behave. Do they use the benches? Are there kids on bikes, people talking, older couples sitting under trees? That’s the real test of design.

Because urban regeneration isn’t just a technical exercise. It’s a social one. Green infrastructure gives people permission to slow down. To be part of a place rather than just move through it.

It’s easy to talk about planting schemes in terms of square metres and canopy coverage. But the real power lies in how it makes people feel.

Looking Ahead – A Greener Urban Future

There’s a quiet shift happening in British cities. Planners, developers, and landscape architects are treating nature not as a constraint but as a collaborator. Green infrastructure isn’t an afterthought tacked on at the end of a project – it’s driving the design from day one.

We’re starting to see mixed-use schemes where rainwater is harvested and reused on site, where trees are considered structural assets, where biodiversity corridors connect housing estates to riverbanks.

It’s a huge step forward.

The next challenge is maintenance – keeping these systems alive and functioning over decades. That means community engagement, funding models, and long-term stewardship. Otherwise, the risk is shiny new planting that fades within a few years.

But I’m optimistic. Once people experience the benefits of a well-designed green public realm, they rarely want to go back.

Conclusion

Urban regeneration used to mean demolition and rebuild. Now it means reconnection – between people and nature, between water and land, between old and new.

Green infrastructure is at the heart of that. Trees, planting, water – they don’t just make cities look better, they make them work better. They manage floodwater, clean the air, cool the streets, and create places people love.

The power of planting isn’t about aesthetics. It’s about resilience. And that’s the kind of regeneration that lasts.

Killingley Insights is the editorial voice of NT Killingley Ltd, drawing on decades of experience in landscaping, environmental enhancements, and civil engineering projects across the UK.