Striking the Balance: Aesthetics and Functionality in Modern Public Realm Design

Spend five minutes in a public square and you can usually tell whether it works or not. Not in an obvious way – it’s more of a feeling. You’ll see it in how people move, how long they stay, and how comfortably they occupy the space. That feeling rarely comes from chance. It’s the result of a careful balance between aesthetics and functionality.

When those two are in harmony, a place comes alive. When they’re not, no amount of expensive paving or fancy lighting can save it.

Modern public realm projects walk a fine line. They have to look appealing, photograph well, and win over local councils, but they also have to withstand heavy footfall, unpredictable weather, and limited maintenance budgets. It’s a constant negotiation between design ambition and practical necessity.

Great public realm design doesn’t choose between beauty and purpose – it finds a way for each to strengthen the other.

Why This Balance Matters

Public spaces serve everyone – from commuters cutting across a plaza to families spending a summer afternoon in a park. They have to accommodate movement, rest, commerce, and play, often within the same footprint.

That means they can’t just be pretty backdrops. A visually stunning space that’s uncomfortable, confusing, or fragile won’t last long. Equally, a hyper-functional design that ignores aesthetics becomes soulless, discouraging the very engagement it was meant to promote.

In Britain, the best examples tend to be those that understand context. The weather, materials, culture, even local habits – all shape what “balance” means for a given place.

If you want a deeper look at how this principle fits into larger regeneration strategies, see our section on public realm and urban regeneration.

What We Mean by Aesthetics

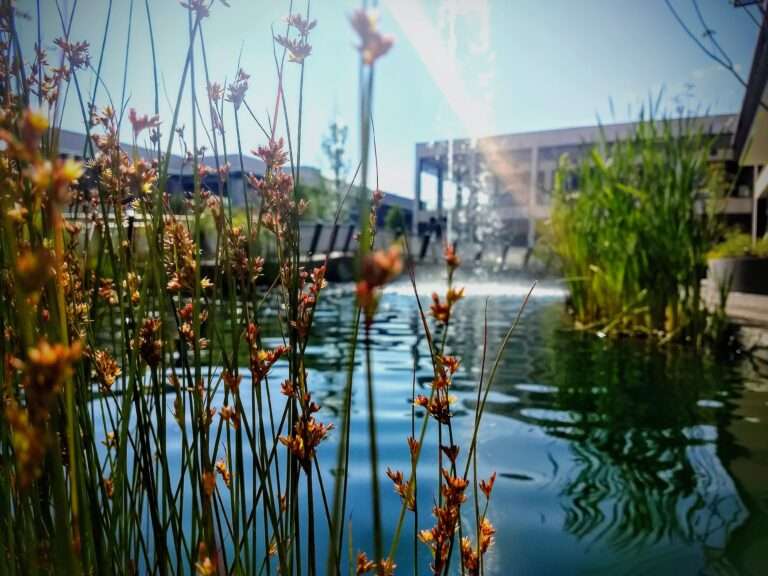

Aesthetics are about more than good looks. They shape mood, rhythm, and emotion. The grain of a paving stone, the warmth of light on wet surfaces, the sound of water masking traffic – these details influence how we feel in a space.

But aesthetics aren’t universal. What feels right in a Georgian square in Bath wouldn’t suit the industrial riversides of Sheffield. Successful designers read the visual language of a place and extend it, rather than overwriting it.

You’ll often find that restraint plays a bigger role than flamboyance. A single line of trees can bring order to chaos. A shift in paving tone can subtly guide pedestrians without a single signpost.

Good aesthetics are invisible – not in the literal sense, but in the way they feel inevitable once you see them.

What We Mean by Functionality

Functionality is the backbone – how a space works under real conditions. It’s about comfort, durability, accessibility, and maintenance. It means surfaces that drain well, routes that make sense, and furniture that invites people to linger rather than pass through.

A design might win awards for innovation, but if the benches are too cold to sit on, or if the fountain floods the pathways every winter, it’s failed. Functionality isn’t glamorous, but it’s what gives beauty its staying power.

It also includes inclusivity. A functional public space is one that everyone can use with equal ease – no hidden steps, no confusing gradients, no token ramps shoved in after the fact.

The Danger of Designing for the Photograph

There’s an unspoken pressure in public realm projects to create that “hero shot” – the image that looks great on a tender document or local press release. Wide, empty plazas photographed at sunset. Perfectly symmetrical paving.

The trouble is, life doesn’t behave like a render. People move bins, park bikes, spill coffee, push prams. Weather leaves its mark. Surfaces stain and age.

I’ve seen spaces designed around the camera rather than the user. They win awards in year one, then need costly refits by year three. True design longevity lies in how it performs when the novelty fades – when the rain hits sideways and the commuters are rushing through in the dark.

That’s when functionality earns its keep.

Designing for Human Behaviour

There’s a concept in urban design called “desire lines” – the informal paths people create when they ignore the intended routes. You see them on university campuses, in parks, even across new plazas where the layout didn’t match human instinct.

Good designers anticipate those movements rather than fight them. They study flow. They watch how people naturally navigate corners, crossings, and thresholds. Then they design accordingly.

When design respects behaviour, function becomes beautiful in itself. A perfectly positioned bench, a kerb that disappears seamlessly into the pavement, a lighting pole placed exactly where it feels right – these details may seem small, but together they define usability.

Materials – Where Looks and Longevity Collide

Materials can make or break a scheme. Too cheap, and it dates fast. Too refined, and it won’t survive everyday use. The trick lies in selecting finishes that weather well and age gracefully.

Here’s where that balance is clearest:

| Material | Aesthetic Value | Functional Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Yorkstone paving | Classic British character | Expensive, but durable and repairable |

| Resin-bound aggregate | Smooth, modern look | Excellent drainage but can discolour |

| Corten steel | Industrial tone, rich patina | Must be detailed to prevent staining nearby surfaces |

| Hardwood seating | Warm, tactile | Needs treatment and regular care |

| Concrete benches | Minimal, durable | Can feel cold and uninviting without detail or planting nearby |

The best public spaces use a mix – tactile where people touch, durable where they tread, expressive where they look. It’s a hierarchy of performance.

Lighting – Safety Meets Atmosphere

Lighting is often the unsung hero. It shapes how a place feels after dark, determining whether it’s inviting or intimidating.

The balance here is subtle. Over-light and the atmosphere disappears – the space becomes flat and harsh. Under-light and people avoid it altogether. Warm colour temperatures, layered intensities, and concealed fixtures tend to work best.

Take London’s South Bank. The walkway glows softly rather than glaring. The lights highlight structure and planting, but never overwhelm. That’s aesthetic functionality in action – lighting that serves safety and beauty in equal measure.

Maintenance – The Real Test of Design

Designers rarely get applauded for maintenance planning, but they should. A space that’s easy to maintain is one that stays attractive.

There’s no point specifying imported stone if it stains with the first coffee spill. No use installing planters if there’s no irrigation or staff to tend them.

Maintenance-friendly design might sound dull, but it’s what makes regeneration sustainable. Stainless fittings that resist corrosion. Modular paving that can be lifted for utilities without scarring the pattern. Locally sourced materials that can be replaced easily.

If the practical side is ignored, the aesthetic side doesn’t stand a chance.

The British Context – Climate, Culture and Constraints

You can’t design public space in Britain without thinking about rain. Or frost. Or the occasional festival crowd. Our climate and culture demand resilience.

In London, projects like King’s Cross have embraced robust materials – granite, brick, and steel – softened with planting and water features. In smaller towns, budgets are tighter, so designers lean on simplicity and local stone.

One thing that’s changing is public expectation. People now want spaces that are both sustainable and attractive. That means rain gardens instead of drains, native planting instead of decorative exotics. The aesthetics of sustainability are becoming the new normal.

The Role of Public Art

Public art is one of those elements that can tip the balance either way. When done well, it anchors identity. When forced, it becomes clutter.

Integrated art tends to work best – patterns in the paving, sculptural seating, lighting installations that respond to movement. Art that emerges from the fabric of the space rather than being plonked into it.

I remember a small market square in the Midlands where local artists designed the drainage grilles to reflect the town’s history in ironwork. It was subtle, functional, and meaningful. That’s design synergy at its best.

Functionality as a Kind of Beauty

There’s a quiet elegance in things that simply work. A well-designed bench doesn’t just look good; it sits at the right height, catches the sun at lunchtime, and drains after rain.

It’s easy to underestimate that sort of beauty – the understated kind. But for those who spend time in the space every day, that’s what makes it memorable.

Form and function don’t need to compete. They’re partners. And when one strengthens the other, the space feels effortless.

The Future of Public Realm Design

Looking ahead, this balance will only get trickier. Climate adaptation, accessibility, and biodiversity are adding new layers to the brief. Designers now have to consider runoff, shade, pollinator habitats, and social inclusion – all while keeping things visually cohesive.

Digital design tools and modular materials are helping, but the human element still matters most. Walk the space before drawing it. Visit in the rain. Watch how people use it.

Because in the end, no algorithm can replace intuition – the kind that understands when beauty and practicality have truly met in the middle.

Conclusion

Modern public realm projects are measured not by how they open, but by how they endure. A balance between aesthetics and functionality ensures they can do both – impress at first sight and perform over time.

When public spaces are designed to look good and feel right, they become part of daily life rather than background noise. They host markets, protests, picnics, and memories. That’s what urban design should aim for – not perfection, but permanence with purpose.

In the best examples, you don’t notice the balance at all. You just know the space works.

Killingley Insights is the editorial voice of NT Killingley Ltd, drawing on decades of experience in landscaping, environmental enhancements, and civil engineering projects across the UK.