Making Infrastructure Work Harder for Nature: Integrating Ecological Enhancements into Landscape Schemes

It usually starts with a drawing. A road. A drainage corridor. A compound. Somewhere in the margins, a green line or two. Maybe a note that says “native planting”. Job done? Not quite.

Integrating ecological enhancements into infrastructure and landscape schemes is one of those topics that sounds tidy in principle and messy in practice. Because infrastructure, by definition, is about movement, service, access, efficiency. Ecology, on the other hand, likes time, continuity, and being left alone. Getting the two to coexist takes more than goodwill.

I’ve seen projects where the ecological bit felt like an apology. And others where it quietly became the strongest part of the scheme. The difference wasn’t budget or planning pressure. It was intent, timing, and a willingness to treat ecology as part of the system rather than decoration.

That’s what this article digs into. Not theory. Not box-ticking. Just the practical reality of folding ecological enhancements into roads, drainage, utilities, public realm, and large-scale landscapes across the UK. Properly. Without it turning into a bit of a faff.

Why infrastructure projects struggle with ecology

Let’s be blunt. Infrastructure is often hostile to nature. Linear corridors slice through habitats. Hard edges dominate. Timelines are tight. Interfaces are complex. Everyone’s focused on “getting it in the ground”.

Ecology tends to arrive late to that party.

By the time ecologists are asked for input, alignments are fixed, levels are signed off, and construction methodology is locked in. At that point, enhancement options shrink dramatically. You’re left squeezing biodiversity into the leftovers.

That’s not a criticism of project teams. It’s just how programmes tend to run. Roads and utilities feel urgent. Green stuff can wait. Or so it seems.

But here’s the catch. Retrofitting ecological enhancements into infrastructure schemes nearly always costs more, takes longer, and delivers less. Early integration feels slower at first. Then it saves time everywhere else.

What integration really means on the ground

Integration isn’t about adding more features. It’s about making existing elements do more than one job.

Take a highway verge. Traditionally, it’s just there to separate carriageway from boundary. With a bit of thought, it becomes a pollinator corridor. Or a buffer protecting adjacent habitat from runoff and disturbance.

Or drainage. A SuDS basin doesn’t have to be a sterile bowl fenced off with warning signs. With the right profiles and planting, it becomes wetland habitat, water storage, and landscape feature in one. No extra land take. Just smarter use of what’s already there.

Integration is about asking, repeatedly: can this element work harder?

Sometimes the answer’s no. Fine. But often, it’s yes, if you catch it early enough.

Landscape schemes as the glue

Landscape is where infrastructure and ecology tend to meet, whether anyone planned it that way or not.

Soft landscape buffers hide utilities. Bunds screen roads. Open space stitches phases together. These are already transitional zones, which makes them perfect candidates for enhancement.

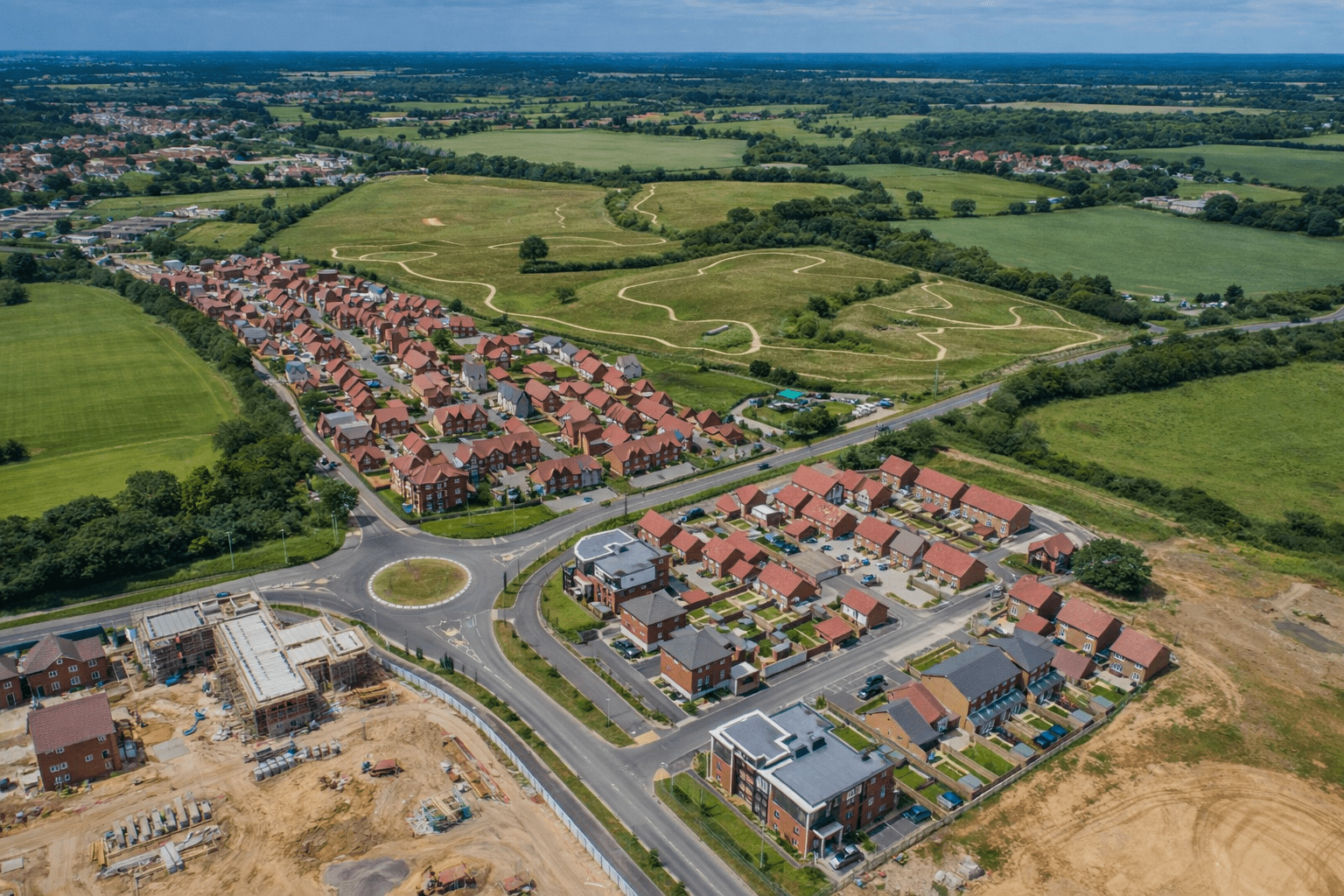

In housing schemes around the Midlands, for example, it’s common to see attenuation features wrapped in amenity grass because it’s easy to maintain. Swap that for species-rich grassland, manage it properly, and suddenly you’ve increased biodiversity units without changing the footprint.

I find landscape architects who understand this tend to get better buy-in from engineers too. Because the landscape isn’t fighting the infrastructure. It’s supporting it.

The timing problem, revisited

Worth coming back to this, because it’s the single biggest factor in success or failure.

When ecological enhancements are considered during feasibility and outline design, options are wide open. Alignments can shift slightly. Levels can be tweaked. Features can be stacked.

Leave it until reserved matters or discharge of conditions and you’re negotiating around fixed constraints. Every idea becomes a compromise.

It’s a bit like trying to reorganise a kitchen once all the cabinets are installed. You can do it. Sort of. But you’ll always wish you’d thought about it sooner.

Infrastructure doesn’t have to be grey

There’s an assumption that infrastructure equals concrete and steel. But look closer and there’s usually plenty of opportunity.

Rail corridors, for instance, are often some of the longest continuous green routes in the country. Managed badly, they’re ecological deserts. Managed well, they’re wildlife highways.

Same goes for highways. Margins, embankments, cuttings, and underpasses all have potential. I’ve seen bat roost features integrated into bridge structures so neatly you’d miss them if you weren’t looking.

And then there are utilities. Easements don’t have to be sterile. With the right species selection, they can support low-growing habitats that don’t interfere with access or safety.

The role of metrics and evidence

At some point, someone asks for proof. How do we know this is working?

That’s where metrics come in. Biodiversity Net Gain has pushed this conversation forward faster than anything else in recent years. Love it or loathe it, it forces clarity.

You can no longer wave vaguely at “enhancement”. You need to show uplift. Area, condition, distinctiveness. Numbers.

This has had an interesting side effect. Infrastructure teams are now more willing to engage with ecology earlier, because late changes affect the metric outcome. And metrics affect viability.

When enhancements are baked in from the start, achieving net gain becomes less painful. Sometimes even straightforward.

A quick look at common integrated features

Not a tidy list. Just examples that crop up again and again.

- Swales planted as wet grassland rather than mown turf.

- Road embankments seeded with native meadow mixes suited to local soils.

- Culverts designed with ledges to allow mammal movement.

- Retaining structures incorporating crevices for invertebrates.

- Noise bunds shaped and planted as woodland edge habitat.

None of this is revolutionary. It’s just considered.

Maintenance, the unglamorous bit

No one gets excited about maintenance plans. But they make or break integrated ecology.

Infrastructure maintenance teams are often geared towards safety and access, not biodiversity. Asking them to manage habitats without support is setting everyone up to fail.

Successful schemes align ecological management with existing regimes where possible. Or they provide clear, simple guidance that doesn’t require specialist knowledge.

I’ve seen schemes where enhancement areas were quietly reverted to short grass because “that’s how we’ve always done it”. Not out of malice. Just habit.

Clear handover matters. So does budget. If no one’s paying for management, it won’t happen. Simple as that.

Addressing the usual questions

Does integration slow projects down?

In my experience, no. It tends to smooth later stages. Early discussions take time, yes. But they prevent redesigns, objections, and condition disputes down the line.

Is it only relevant to large schemes?

Not really. Smaller infrastructure projects often have more flexibility. A single access road or drainage run can still deliver meaningful enhancement if it’s thought through.

What about safety and standards?

Critical point. Ecological features must comply with highway standards, drainage requirements, and asset protection rules. Integration isn’t about compromising safety. It’s about working within constraints intelligently.

UK context matters

British infrastructure has its quirks. Narrow corridors. Historic boundaries. Mixed land ownership. Weather that never quite behaves.

All of this affects how enhancements perform. A planting scheme that works in southern England might struggle further north. Clay soils behave differently to chalk. Flood risk changes everything.

Local knowledge counts. There’s no one-size-fits-all template that survives first contact with site conditions.

Joining the dots across sites

That’s the point where a specialist delivery approach stops being “nice to have” and becomes the difference between a scheme that performs and one that quietly unravels after handover. In practice, the teams who get the best outcomes are the ones focused on delivering ecological enhancements across development sites in a consistent, buildable way – aligned with programme, access, safety requirements and long-term maintenance.

Here’s where integration gets interesting at scale.

When multiple infrastructure and landscape schemes are planned across an area, individual enhancements can link up. A road scheme here. A housing site there. A drainage upgrade down the valley.

Suddenly, you’re not just improving individual plots. You’re creating networks. Corridors. Catchment-scale benefits.

This only happens when teams talk to each other. And when someone takes responsibility for seeing the bigger picture.

It’s one of the reasons why experienced contractors and landscape specialists focus on delivering ecological enhancements across development sites rather than treating each project in isolation. Continuity matters.

The human factor

Worth mentioning, because it’s often overlooked.

People like green infrastructure when it’s done well. Residents use it. Walk through it. Sit near it. It becomes part of daily life.

Poorly integrated ecology, by contrast, feels awkward. Overgrown in the wrong places. Underused. Occasionally resented.

Designing with people in mind doesn’t dilute ecological value. It often strengthens it. Disturbance is inevitable. Better to manage it than pretend it won’t happen.

When things don’t go to plan

No scheme is perfect. Weather intervenes. Contractors change. Species fail to establish.

The best projects allow for adaptation. Reseeding. Reprofiling. Tweaks based on monitoring.

Rigid schemes tend to break. Flexible ones evolve.

I was going to say “nature finds a way”, but that’s a bit Hollywood. More accurately, nature responds to what you give it. Good inputs matter.

Pulling infrastructure and ecology together

At its best, integrated ecological enhancement makes infrastructure feel lighter. Less imposed. More settled into its surroundings.

Roads feel less harsh. Drainage feels purposeful. Landscapes feel coherent rather than ornamental.

And crucially, environmental gains can be demonstrated, defended, and built upon.

It’s not about grand gestures. It’s about lots of small, sensible decisions made early, then followed through.

Final thoughts

Integrating ecological enhancements into infrastructure and landscape schemes isn’t a luxury anymore. It’s becoming a baseline expectation.

The projects that do it well don’t shout about it. They just work better. For planners. For communities. For wildlife.

And for the teams delivering them, it’s often less stressful than firefighting late-stage ecological problems.

Which, frankly, is reason enough.

Killingley Insights is the editorial voice of NT Killingley Ltd, drawing on decades of experience in landscaping, environmental enhancements, and civil engineering projects across the UK.