Reed Bed Systems Explained: Natural Water Treatment for Sustainable Sites

It’s funny how often people talk about water treatment as if it all has to involve concrete tanks, clattering pumps, long pipes, all that kit you see behind chain-link fences near industrial estates. There’s another way. Something quieter, greener, and far nicer to look at when you’re walking a dog on a foggy Tuesday morning in Derbyshire. Reed bed systems. They’ve been around for decades, but developers and land managers now seem to be rediscovering them, which isn’t surprising with the push for sustainable schemes.

Anyway, let’s get into it… or rather wander into it, because explaining them usually goes in circles. Fine by me.

Introduction: Why Reed Beds Keep Popping Up in Modern Schemes

Every so often you notice a pattern when you’re out on site. New housing developments near Nottingham, school expansions around Worcestershire, or retrofits to old farmyards that still carry an oily smell from the 80s. More and more of them are slipping reed beds into their drainage strategies.

Odd thing is, most people drive past and don’t even clock them. They just see a patch of tall grass waving about in the wind and think it’s a bit of wet ground nobody wanted to deal with.

But there’s plenty going on underneath those stems. Microbes, root systems, controlled flows — all doing a job that would otherwise need expensive mechanical equipment. Reed beds clean water in a way that feels gentle on the surface while being surprisingly precise underneath. Not perfect, of course. Nothing is. Still, they’re dead good for the right sites.

I was going to compare them to nature reserves, but that sounds over the top. Let’s just say they borrow a few tricks from wetlands and leave it there.

If you want to see where the practical side of this service sits in the broader context, have a look at the work we provide on reed bed installation and refurbishment within our earthworks programmes.

How Reed Beds Work (in Plain, Everyday Language)

Trying to explain reed beds without drifting into jargon is a bit of a faff. So here’s the stripped-back version.

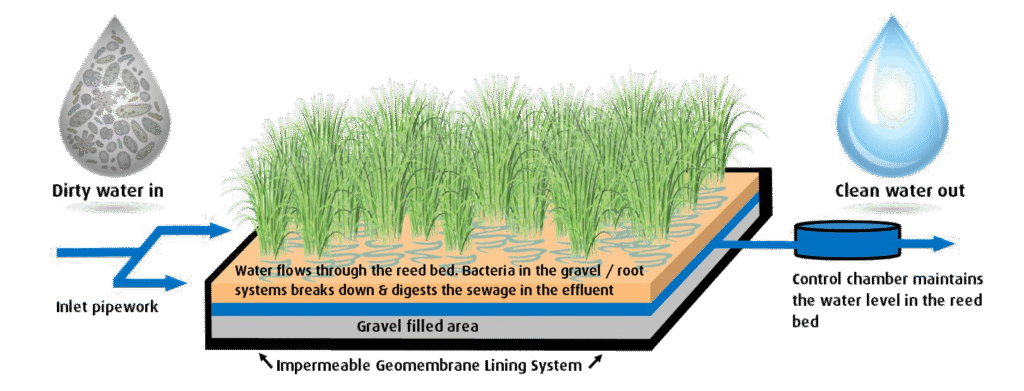

Water enters at one end, moves through a bed of gravel, sand or engineered media, and slowly travels through the root zone. That’s where the magic happens – though I probably shouldn’t say magic when we’re talking science.

Reeds push oxygen down into their roots. That oxygen feeds bacteria that cling onto bits of media underground. Those bacteria break down pollutants. Organic matter gets digested. Nutrients get converted into less harmful forms. Suspended solids settle out. That’s the gist.

It isn’t as quick as blasting water through a treatment tank, but for sites with predictable flows, it’s steady and quietly effective.

Sometimes I find I oversimplify it, then swing the other way and overcomplicate it. So a couple of practical points:

- Vertical flow beds suit sites where you want regular wet-dry cycling. They’re good for ammonia removal.

- Horizontal flow beds keep everything submerged and work steadily without much fuss.

Reed beds don’t like being overloaded, and they’re not great with sudden surges of highly contaminated water. Most developers understand this, but you’d be surprised how many times a design arrives with unrealistic figures and someone has to gently break the news.

Why Developers Lean Toward Reed Beds Now

Years ago, reed beds were seen as quirky add-ons for eco-villages. Very “1990s countryside centre” vibes. That’s shifted. These days, they’re viewed as workable parts of SuDS strategies, especially when planners dig their heels in about achieving biodiversity net gain.

Some reasons feel obvious, others slightly less so.

For a start, reed beds blend in with green spaces. Nobody complains about looking at a bed of Phragmites waving about. It’s much easier to sell that idea to residents than a fenced-off treatment unit humming away.

They also handle everything from domestic wastewater on small rural sites to treating surface water run-off from industrial yards around Sheffield or Leicester. Long life span too, if they’re maintained. And they’re forgiving — up to a point. I mean… not indestructible, but more robust than many expect.

Oh, and running costs tend to be low. No energy bills for aeration, no machinery cycling on and off, none of that “engineers called out at 2am because a pump tripped” nonsense.

Typical Uses (This Bit Always Surprises People)

Reed beds slip into all sorts of places. I sometimes forget how wide-ranging the applications are until I scribble a list out. Here are a few examples:

- Treating effluent from small settlements or holiday parks in places like the Peak District.

- Polishing wastewater from treatment plants to get that last bit of quality improvement.

- Managing run-off from farms, equestrian centres, and similar sites.

- Cleaning up highway drainage where hydrocarbons are floating about.

- Helping older industrial sites meet modern discharge limits.

Odd thing is, once a reed bed is in place and thriving, many people assume it was always there. Nature has a habit of blending things in faster than you’d think.

A Quick Table for Comparisons (Nothing Flashy)

Here’s a simple table. Nothing academic. Just the kind of thing you might sketch when explaining options to a client on a wet day in Doncaster.

| Feature | Reed Bed System | Mechanical Treatment (General) |

|---|---|---|

| Energy use | Very low | Moderate to high |

| Visual impact | Natural look | Industrial infrastructure |

| Maintenance needs | Periodic checks, vegetation care | Regular servicing, equipment upkeep |

| Longevity | 20+ years with good care | Varies, equipment lifespans shorter |

| Noise | Silent | Can include motors, pumps |

| Biodiversity value | High | Very low |

Some engineers wince when you simplify things that much, but it serves its purpose.

Design Considerations That Matter (And a Few People Miss)

Flow rate is everything. Too fast and you lose treatment efficiency. Too slow and you get stagnation. Site gradient also matters, though I’ve seen people overthink it to the point of paralysis.

Planting density plays a role. Start sparse and you’ll wait ages for a full cover. Start too dense and the first winter storm will flatten everything and leave it looking like a bad haircut. Somewhere in the middle tends to work.

Pre-treatment is another big one. Reed beds like water that’s reasonably settled. Not pristine, just not full of huge solids. A small settlement tank or chamber usually does the trick.

Climate can be mentioned, though in the UK the difference between Cornwall and Northumberland isn’t huge from a reed bed perspective. Cold spells slow things down. Heat waves kick things along. Same story as most biological systems.

Construction: How It’s Put Together

There’s a tendency to imagine reed beds as simple holes in the ground. Something you could dig with a mini-digger and call finished. That’s not quite the case.

A well-built reed bed uses liners to keep flows controlled. The media needs precise layering — coarser at the bottom, finer up top. Flow distribution pipes across the inlet to stop short-circuiting. Outlet structures that let you tweak water levels.

It’s a bit like building a very shallow, very controlled garden pond, except you don’t want open water and you definitely don’t want bypass paths forming.

Pipework needs checking for fall. Media needs compacting lightly (just enough). Reeds need planting at the right density and in the right season. Spring tends to be the sweet spot, but I’ve seen successful autumn plantings as well in milder years.

I’m rambling. Let’s move on.

Maintenance: Easier Than People Expect

Reed beds aren’t maintenance-free, contrary to what some old brochures claimed. The maintenance is just simpler.

What usually needs doing?

Clearing inlet screens, occasionally thinning vegetation if the bed gets too dense, checking for signs of clogging, making sure water levels stay within design ranges. Some sites include seasonal cutting, especially where access for surveys is awkward.

The good news is that reed beds don’t rely on complex components. They don’t suddenly fail because a sensor died at the wrong moment. They tend to decline slowly, giving plenty of time for corrective work.

On rural sites, wildlife might interfere — geese in particular have a talent for making a mess of freshly planted beds — but that’s manageable.

FAQs (Because These Always Crop Up)

Do reed beds smell?

Not if they’re working properly. A faint earthy smell at most. If someone complains of odour, it usually means something upstream is off.

Can they freeze in winter?

Surface freezing, yes. Functionally frozen through? Very unlikely in the UK climate. Even in the harsh winter of 2010, most beds I heard about kept ticking over.

How long until they mature?

About one growing season for basic function. Two to three years for full strength. Fortunately they start treating water well before they look fully established.

Are they suitable for housing estates?

Quite often, yes. They’re great for edge-of-site SuDS integration. You wouldn’t drop one in the middle of a tight urban block in Manchester, but fringe developments, business parks, schools — all fair game.

Do they need fencing?

Sometimes. Depends on risk assessments, depth of water, and site usage. Many designs use shallow profiles so formal fencing isn’t required.

Environmental Benefits: More Than People Realise

Reed beds don’t just treat water. They create habitat. Birds, insects, amphibians — the whole cast of wetland dwellers turns up eventually.

It’s odd watching biodiversity targets get met by accident when a reed bed goes in for water treatment, but it happens.

Carbon footprint? Lower than mechanical systems. Operational emissions are close to zero. Embodied carbon still exists, obviously, because liners and media don’t appear from thin air, but overall it’s modest.

And aesthetic value shouldn’t be dismissed. A well-designed reed bed can soften the look of hard-edged developments. That matters when residents take pride in their surroundings.

Practical Examples From Around the UK

Driving along the A52 near Nottingham, you’ll spot reed beds quietly treating run-off from service yards. Up in Cumbria, small tourism sites use them to handle wastewater without spoiling the landscape. Midlands schools lean on them for SuDS credits.

Farmyards in Lincolnshire retrofit them as part of slurry management upgrades.

You get the picture. They turn up everywhere once you start noticing.

When Reed Beds Aren’t a Good Fit

It’s worth saying they’re not miracle solutions. If flows are wildly inconsistent, or contamination levels spike unpredictably, mechanical systems might be better. Sites with almost no space struggle too. And some industrial waste streams simply demand heavy-duty treatment.

I sometimes find myself pushing back gently with clients who want a reed bed because it sounds green. It has to fit the site. When it does, brilliant. When it doesn’t, it’s best to say so.

Closing Thoughts: Why Reed Beds Are Still Growing in Popularity

You know when something just works without making a fuss? Reed beds fall into that category. Quiet achievers.

They won’t replace all mechanical systems. They weren’t intended to. But in the right places — especially developments aiming for long-term sustainability — they’re spot on.

And with more planning authorities wanting nature-based interventions, you’ll likely see many more of them over the next decade, tucked beside new roads, on business parks, behind farm buildings… all the usual places.

Killingley Insights is the editorial voice of NT Killingley Ltd, drawing on decades of experience in landscaping, environmental enhancements, and civil engineering projects across the UK.