Demolition for Landscaping Projects: Clearing the Way for Better Ground, Better Outcomes

Landscaping sounds gentle, doesn’t it? Trees, soil, maybe a bit of wildflower seeding if the planners are feeling generous. But before any of that happens, there’s often a far messier phase. Concrete slabs that have seen better days. Old farm buildings half-collapsed but still stubbornly standing. Redundant yard areas, access tracks, kerbs, walls, pads, services poking out where they shouldn’t.

In my experience, this early demolition stage is where projects are either set up properly… or quietly compromised.

You wouldn’t build a house on rotten foundations. Same logic applies to landscape schemes. If the site isn’t cleared properly, if the ground conditions aren’t reset, everything that follows becomes harder than it needs to be. Drainage behaves oddly. Levels never quite work. Contractors end up bodging around obstacles that should have been dealt with at the start.

And yes, it can feel counter-intuitive. Spending time and money removing things before you can add anything new. But get this bit right and the rest of the project flows. Miss it, and you’re firefighting all the way through.

What demolition means in a landscaping context

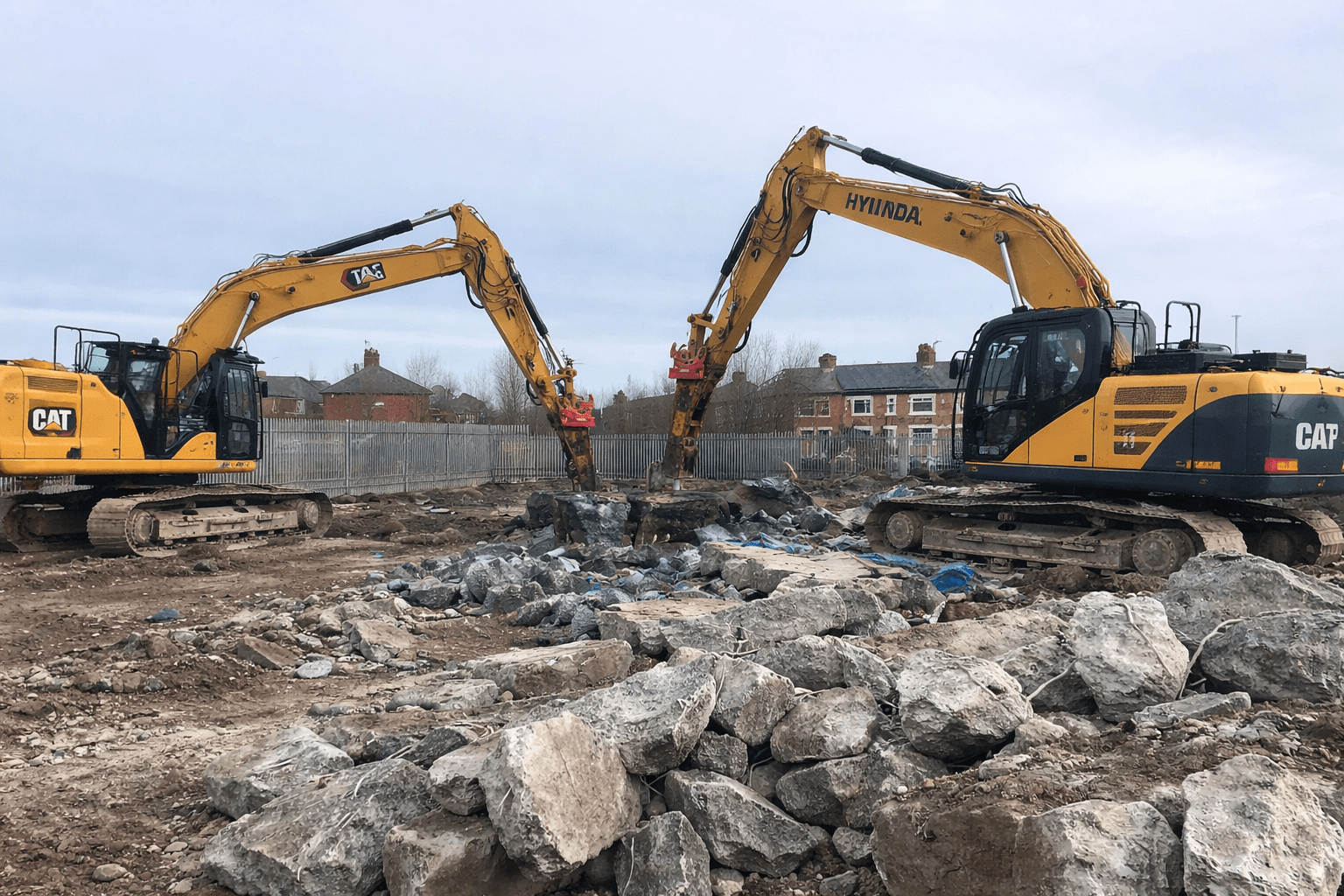

Forget the image of a wrecking ball swinging into a tower block. Demolition for landscaping is more surgical than dramatic. It’s about removing what no longer serves the site so that something better can take its place.

That might mean breaking out old hardstandings from a former industrial yard in Derbyshire. Or carefully dismantling redundant agricultural sheds on the edge of a village development. Or lifting concrete paths in a public realm scheme where permeability and SuDS now matter more than neat straight lines.

Often it’s a combination of tasks rather than one big hit.

- Concrete slabs and pads broken up and removed

- Kerbs, edging, steps and ramps taken out

- Retaining walls dismantled where levels are changing

- Old foundations grubbed up so roots and services can run freely

Each job has knock-on effects. Remove a slab and suddenly drainage options open up. Take out a wall and sightlines change. Clear a building footprint and the soil beneath tells you a story about compaction, contamination, or historic use.

Funny thing is, demolition tends to reveal more than it removes.

Why demolition is so often underestimated

Partly, it’s because people see demolition as destructive rather than constructive. It’s easy to think of it as a necessary evil rather than an enabling step. I used to think that too. Then you see the difference between sites where demolition was rushed, and those where it was planned with the end landscape in mind.

Rushed demolition leaves problems behind. Bits of concrete buried because “no one will see it”. Services cut and capped badly. Levels left uneven because the excavator moved on too quickly.

Planned demolition does the opposite. It resets the site. Clears the slate properly.

And no, that doesn’t mean over-engineering it. It means understanding what’s coming next. Where paths will run. Where trees will go. Which areas need free-draining ground and which can cope with heavier loads.

In landscaping, demolition isn’t the end of something. It’s the beginning. Or maybe the middle. You know what I mean.

Common structures removed before landscaping works

Every site has its own quirks, but certain things crop up again and again, especially across the Midlands.

Old concrete yards are probably top of the list. Former factories, depots, even schools with expanses of hardstanding that made sense decades ago but now work against modern drainage and biodiversity goals.

Then there are agricultural remnants. Barn bases, silage clamps, feed stores. Solid bits of kit that did a job once, but now sit awkwardly in the way of new planting or access routes.

Residential sites bring their own mix. Garages, garden walls, patios laid in the 80s that were never quite level to begin with. I’ve lost count of how many times someone’s said “we’ll keep that bit” only to realise later it’s right where the new footpath needs to be.

Infrastructure projects add another layer again. Temporary compounds, haul roads, concrete plinths for cabins or plant. All need to come out cleanly so reinstatement isn’t compromised.

And yes, sometimes it’s just a random lump of concrete in the middle of nowhere. No one knows what it’s for. But it’s there. Waiting.

Hardstandings and why they’re such a headache

Hardstandings deserve a section of their own. They look simple enough. Flat concrete. Maybe a bit cracked. Surely just break it up and cart it away?

Not always.

Underneath, you often find layers. Hardcore. Old drainage runs. Sometimes contamination, depending on historic use. Removing the slab is only part of the job. Dealing with what’s beneath it is where experience matters.

From a landscaping point of view, hardstandings cause three main problems.

First, water. Impermeable surfaces push water elsewhere, often to places you don’t want it. Removing them allows water to soak away naturally or be managed properly through SuDS features.

Second, roots. Trees and shrubs need space. Leaving fragments of concrete below ground limits root spread and long-term plant health.

Third, levels. Hardstandings are rarely at the right finished level for landscaped areas. Keeping them usually means awkward steps, ramps, or sudden drops that never quite feel right.

So while it’s tempting to retain them for cost reasons, in practice they often cost more later on.

Obstructions you don’t notice until you try to landscape

Here’s the thing. You can walk a site ten times and still miss what’s lurking just below the surface. Old fence posts snapped off at ground level. Foundations from a long-gone structure. Drain covers that don’t appear on any drawing.

I’ve seen landscape teams turn up ready to start planting only to hit concrete within the first spade depth. That’s when projects stall. Planting schedules slip. Everyone looks at each other. Someone sighs.

Proper demolition work reduces those surprises. Trial holes. Careful breaking out. Not assuming that just because it’s grassed over, it’s clean beneath.

Sites have memories. Demolition is how you erase the bits you don’t want carried forward.

Demolition and soil health – an overlooked connection

Soil often gets treated as something you deal with after demolition. But really, the two should be thought about together.

Heavy demolition equipment can compact soil badly if it’s not managed. Likewise, poor demolition can leave rubble mixed through the topsoil layer, which then causes problems for planting and drainage.

Good practice involves stripping and storing topsoil separately. Protecting it while demolition happens. Then reinstating it once the heavy work is done.

I find that when demolition contractors understand the landscaping intent, outcomes improve massively. It’s not just about clearing. It’s about leaving the ground in a condition that can be worked with.

That bit of coordination saves weeks later. Probably more.

Health, safety, and the not-so-glamorous side of it all

Let’s be honest. Demolition is noisy, dusty, and sometimes a bit of a faff. But it’s also tightly regulated for good reason.

Asbestos still crops up, especially in older farm buildings and post-war structures. Utilities need tracing and isolating properly. Public sites require careful segregation so no one wanders into a work zone because they thought it was a shortcut.

All of that needs managing before the first bucket touches concrete.

In landscaping projects tied to public realm or infrastructure works, safety planning is often as complex as the demolition itself. Traffic management. Working near live services. Coordinating with other trades who are itching to get started.

It’s not glamorous work. But when done well, you barely notice it afterwards. Which is kind of the point.

Planning demolition as part of the wider landscape programme

Demolition shouldn’t be an afterthought tagged on to the front of a landscaping contract. It works best when it’s planned as part of the overall programme.

That means understanding sequencing. What comes out first. What needs temporary access. Which areas can be cleared early and which must wait until services are diverted or surveys completed.

In Derbyshire and the wider East Midlands, this often involves working around weather as much as anything else. Winter demolition on clay soils is… character building. Leave the ground open too long and it turns into a quagmire. Time it right and you can move smoothly into earthworks and planting when conditions improve.

The best projects I’ve seen treat demolition, earthworks, and landscaping as one continuous process rather than three separate jobs stitched together.

Choosing the right approach for different sites

No two sites demand the same demolition approach.

Urban regeneration schemes often require careful, phased removal to minimise disruption. Noise restrictions. Dust control. Working around pedestrians and traffic.

Rural sites might allow more freedom but bring other challenges. Soft ground. Access limitations. Ecological constraints. Nesting seasons, protected species, the usual list.

Brownfield sites add another layer again. Contamination. Unexpected structures. The occasional “what on earth is that?” moment when something odd turns up during breaking out.

This is where local knowledge helps. Knowing how typical Derbyshire soils behave. Understanding the kinds of structures you’re likely to encounter based on land use history. It all feeds into smoother delivery.

When demolition enables better design

Here’s a slightly philosophical point. Removing constraints can improve design quality. Sounds obvious, but it’s easy to forget.

I’ve seen landscape designs compromised because an old slab was kept to save money. Paths bent awkwardly around it. Planting squeezed into leftover spaces. The whole thing felt… compromised.

Remove the slab and suddenly the design breathes. Lines make sense. Spaces flow. Maintenance becomes easier. Users feel it, even if they can’t articulate why.

So demolition isn’t just about practicality. It shapes outcomes in subtle ways.

And if you want to see how this ties into wider site preparation work, there’s more detail on our demolition service in Derbyshire and how it supports landscape-led schemes across the region.

Frequently asked questions that come up time and again

Do we really need to remove all existing structures?

Not always. Some elements can be reused or repurposed. But decisions should be made deliberately, not by default. If something stays, it needs a clear role in the finished landscape.

Can demolition be phased to save time?

Yes, and often should be. Clearing key areas early allows other works to start while demolition continues elsewhere. Sequencing is everything.

What about sustainability and waste?

Concrete and hardcore can often be crushed and reused on site. That reduces waste and vehicle movements. It’s not suitable everywhere, but when it works, it’s spot on.

Is demolition noisy?

Short answer, yes. But impacts can be managed through timing, equipment choice, and communication with neighbours. Most issues arise when expectations aren’t set early.

How does demolition affect project cost?

Poor demolition increases costs later. Proper demolition upfront usually saves money overall. Not always obvious on paper, but very obvious on site.

The bit people forget to talk about

Demolition can be oddly satisfying. There’s something about seeing a cluttered, constrained site opened up. Space appearing where there was none. Potential becoming visible.

I know that sounds a bit poetic for breaking concrete, but spend enough time on sites and you’ll see it too.

Once the rubble’s gone, the noise dies down, and you’re left with bare ground ready for the next phase. That’s when landscaping really begins. And that moment relies entirely on what happened before.

Conclusion – clearing ground, clearing problems

Demolition for landscaping projects isn’t glamorous. It’s noisy, messy, and often taken for granted. But it’s also one of the most important stages in delivering successful outdoor spaces.

Remove the wrong things, or remove them badly, and problems linger. Do it properly and everything that follows becomes simpler. Drainage behaves. Planting thrives. Designs make sense.

In the end, demolition isn’t about destruction. It’s about preparation. Clearing away yesterday’s decisions so tomorrow’s landscapes have room to grow.

And in this line of work, that’s time well spent.

Killingley Insights is the editorial voice of NT Killingley Ltd, drawing on decades of experience in landscaping, environmental enhancements, and civil engineering projects across the UK.